Orthodox Christians

by Tatiana Osipovich

The Russian Orthodox Church in Oregon traces its history back to the Russian Orthodox mission to Alaska, which was established in the 1790s to serve both Russian traders and newly converted Alaskan natives. From its first North American outpost, the church soon extended its missionary efforts southward, to such cities as New Orleans and San Francisco, where independent Orthodox parishes appeared in the mid-1800s, and then eastward, to New York City, whose first Orthodox parish was established in 1870 (Cole 1975, 11).

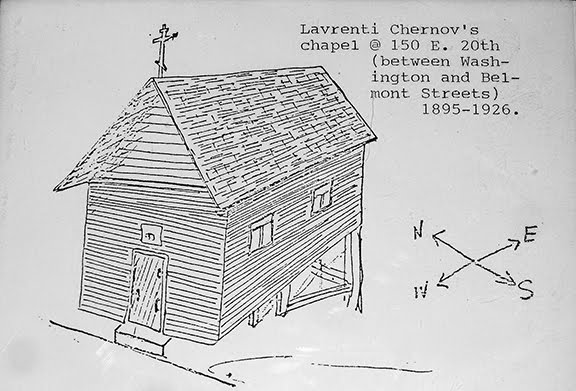

After Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, the Russian Orthodox Church in North America continued to grow, serving multi-ethnic immigrant communities of the Orthodox faith that kept arriving from Eastern Europe, Russia and the Middle East. In the late 19th century several different groups of Orthodox immigrants arrived in Oregon, and while their backgrounds varied, they were similar in that they were overwhelmingly poor, illiterate, unskilled or semiskilled peasants, without the means to build their own church. Among these newcomers was an Alaskan of mixed native American and Russian heritage, Lavrenty Chernov (or Chernoff), who later took the legal name Lawrence Stevens. Chernov — he used the name Stevens only for legal purposes — was a common laborer of very modest means, but he was very religious, and his faith inspired him to build a small Orthodox chapel (часовня/chasovnya) in his new hometown, Portland.

Chernov and his Swedish immigrant wife worked very hard, saved some money and bought land on 20th Street in East Portland. A small wooden chapel named after the Holy Trinity was soon built there, becoming the first Russian Orthodox outpost in Oregon. Among the documents held by the Oregon Historical Society is the deed of ownership with which Lawrence Stevens officially transferred the chapel to Rt. Rev. Nicholas, Bishop of Alaska and the Aleutians, on August 14, 1894. Dedicated on February 26, 1895, the Holy Trinity chapel served a small, multi-ethnic community of Russians, Syrians and Serbs for several years, with the Serbs coming to the chapel all the way from Astoria (Cole 1975, 19-21).

After the chapel had served Portland’s Orthodox community for several years, its industrious and devoted founder died, and it fell into disrepair and neglect. One of the reasons for its abandonment was the inability of the city’s three Orthodox ethnic groups — Greeks, Syrians and Russians — to work together. Only in 1908 was the Holy Trinity chapel finally restored by the Greek Orthodox community, which soon realized that the structure was too small for its growing congregation and decided to build a larger church. The new Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church opened its doors in 1910, and Chernov’s little chapel was once again abandoned.

A new chapter in the history of Russian Orthodoxy in Oregon began with the arrival of new immigrants from post-revolutionary Russia in the early 1920s. Most of these newcomers had fled the Bolsheviks and the Civil War by moving first to the Russian Far East and then to China. Originally arriving in Seattle or San Francisco, some of them found employment in Portland, where they had difficulty fitting in, not just with American life, but also with the existing Russian community. The two groups of Russians were distinctly different. The older group consisted mostly of poor, illiterate settlers who disliked Russia’s old regime and sympathized with the Bolsheviks. The new arrivals were better educated, more professional and very anti-Soviet. Due to the social and political differences between the two groups, frictions and conflicts within Portland’s Orthodox community began to emerge. The renewed services in the Holy Trinity chapel were sometimes disrupted by groups of radical Russian old-timers who demanded that the building be used for secular purposes, such as a “Russian Club” (Cole 1975, 41).

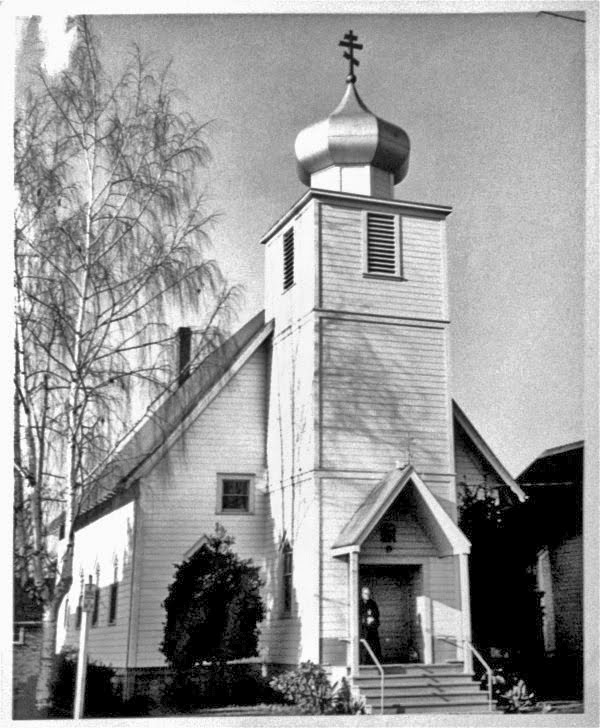

Portland city authorities ultimately ordered the demolition of the Holy Trinity chapel due to its dilapidated condition. But the small Russian Orthodox congregation continued services, first in a temporary house-church, and later in a church building that they purchased from a German Brethren congregation. This former Free Evangelical Brethren Church on NE Mallory Street was purchased in November 1927 and re-registered as “Saint Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church of Portland, Oregon,” retaining this legal name until 1976. In the spring of 1928 a Russian Orthodox cross was placed on the church’s four-sided tower, which was later replaced by a more appropriate Russian gold dome (later painted blue).

St. Nicholas Church served the Russian Orthodox faithful at its location on NE Mallory Street for the next 50 years, seeing no less than 16 pastors come and go during this time. The church became more Russian in its language, customs and liturgical practices as the Greek and Syrian Orthodox communities moved to their own churches, Holy Trinity and St. George, respectively. In March 1970 the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) received autocephaly from its parent church, the Moscow Patriarchate, and like many other OCA churches in the United States, St. Nicholas Church switched to the Revised Julian calendar — so that it celebrated Christmas on December 25 — and began using English in its liturgical services. In 1976 it dropped the word “Russian” from its name.

In the late 1970s, St. Nicholas Church received a new property on Dolph Court in Southwest Portland, where a new parish was established in 1981. Fifteen years later, a new, larger church was erected on this land, and on Palm Sunday 1998, it celebrated its first Divine Liturgy, with 300 faithful in attendance (St. Nicholas’s website).

The OCA is not the only offshoot of the Russian Orthodox Church in Oregon, though. Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the new regime in Russia declared religion to be the “opiate of the people” and embarked on a campaign of destroying churches and persecuting clergy. In this climate, in 1920 Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow (who had previously been a bishop in America) authorized the formation of an independent church administration outside Russia’s borders until the central Church administration could be restored and communication with it reestablished. Exiled bishops set up the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR), which eventually moved its headquarters to New York and continued to regard the Moscow Patriarchate as a puppet of the Soviet regime throughout the existence of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, ROCOR also had an uneasy relationship with the OCA.

Tensions between ROCOR and the Moscow Patriarchate eased after the collapse of the Soviet Union and particularly after Vladimir Putin became president and lobbied for a reconciliation between the two Russian Orthodox churches. On May 17, 2007, ROCOR and the Moscow Patriarchate signed the historic Act of Canonical Communion, restoring the canonical link between the two churches. Importantly, though, the OCA remained independent of its mother church in Russia.

Today, ROCOR has 194 parishes in the United States, compared to about 700 for the OCA. There are only three small churches in Oregon that are part of ROCOR and therefore fall under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate: New Martyrs of Russia Church, in Mulino; St. Innocent of Irkutsk Church, in Rogue River; and St. Martin the Merciful Church, in Corvallis. While OCA churches tend to use the Revised Julian calendar, ROCOR churches follow the old Julian calendar, used in Russia until 1917, in which Christmas is celebrated on January 7.

Selected bibliography:

Cole, David B. Russian Oregon: A History of the Russian Orthodox Church and Settlement in Oregon, 1882-1976. Diss. Portland State U, 1978.

Stokoe, Mark, and Leonid Kishkovsky. “Orthodox Christians in North America.” Orthodox Christians in North America. OCA, 1995 (available on line: http://oca.org/history-archives/orthodox-christians-na).

Tarasar, Constance J., and John H. Erickson, eds. Orthodox America, 1794-1976: Development of the Orthodox Church in America. Syosset, NY: Orthodox Church in America, Dept. of History and Archives, 1975

“The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia – Official Website.” The Russian Orthodox Church Outside ofRussia – Official Website. ROCOR, n.d. Web. 25 July 2014.