Jewish Immigrants

by David Salkowski

Jews from the historic Russian Empire began to arrive in Oregon in the 1880s and continued to come throughout the 20th Century. This migration is a reflection of a large-scale demographic movement of Jews from Eastern Europe to the United States in the past century and a half. This trend began with the ascension of Tsar Alexander III to the throne of the Russian Empire in 1881. While Jews had enjoyed the modest liberalization that had taken place under Alexander II, the new regime saw increased anti-semitic propaganda, new laws restricting Jewish movement, and recurring bouts of pogroms. This persecution, along with a history of poverty and lack of social mobility, drove over 2 million Jews to flee the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1910. Over half of them came to the United States.

Immigration to the United States was unrestricted for Europeans until the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which was created largely in response to the influx of Jews and other immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. While most Russian Jews remained in the Lower East Side of New York City after coming through Ellis Island, many dispersed to various corners of the US, including the Northwest. Most of the Jews who continued to Oregon from New York were self-selected, probably because of Portland’s profile as a growing commercial, rather than industrial city, in contrast to New York (Eisenberg 84). These early, mostly Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants tended to be from rural shtetl backgrounds and were poor and uneducated. However, many of these families, such as the Schnitzers and Directors, quickly achieved success and prominence in Portland.

A small but significant offshoot of the earliest enclaves of Jewish emigrants from the Russian Empire founded a handful of utopian communities in the United States. One such settlement, New Odessa, was created in 1883 in Oregon, between Roseburg and Ashland, by a small group of young Jews from Odessa, Russia (now Ukraine). They were part of a movement known as Am Olam, a socialist, Jewish organization dedicated to returning to communal, agrarian living. This group of about fifty Russophone Jews lasted some five years. Another similar community was founded in North Dakota in 1883, and after nine years of hardship, most families left, several of them settling in Portland in 1892.

While most immigrants to Portland did so for the specific opportunities of the city or to reunite with family, others arrived in Portland under the direction of national organizations. In 1901, the Industrial Removal Office (IRO) was instituted in response to overcrowding in the Jewish quarter of New York City. The IRO distributed Jews to different cities throughout the US. According to Polina Olsen, between 1901 and 1917, 430 Jews (though Lowenstein puts this number at 858), almost entirely emigrants from the Russian Empire, joined the Portland community.

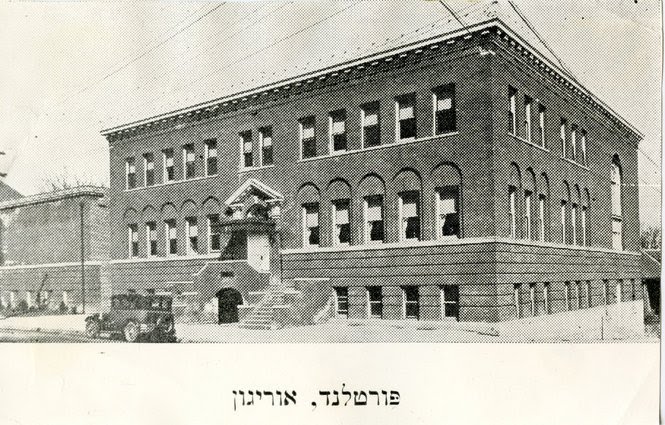

The Eastern European Jews concentrated mainly in Southwest Portland around the Neighborhood House, then located on 1st Street and Porter Avenue. This was the central hub of the Portland Jewish community for many years until the creation of the South Auditorium Urban Renewal District in 1958. The newcomers contributed to existing Jewish institutions founded by early German Jews in the area and created some of their own, such as Neveh Zedek Synagogue, later to be integrated into Neveh Shalom. The bulk of the Jewish community remained in the Southwest part of Portland, creating a base for immigrants who would arrive during the Soviet era.

The next large wave of Russian Jews to Oregon occurred in the final decades of the Soviet Union. Though many Jews fled the Soviet Union in the intervening years, after the Russian Revolution and World War II, these migrants were largely undocumented and it is unlikely that many reached Oregon. Emigration from the Soviet Union was officially prohibited until the 1970s. While all religions were subject to persecution in the Soviet Union, since “Jewish” was listed as a nationality on internal passports, Jews were particularly vulnerable to such marginalization. Jews were often systematically barred from professional advancement and many educational institutions. While Stalin publically condemned anti-Semitism, under his regime Jews were targeted as “anti-Soviet,” or “Zionist conspirators” (Levin 685).

Under Brezhnev’s leadership, selective emigration was permitted to Jews beginning in 1971. Several international events are responsible for this, including the Brussels Conference, which demonstrated the solidarity of Jews worldwide to those in the Soviet Union, and US efforts towards detente with the Soviet Union. In 1972, President Nixon authorized a treaty expanding trade with the Soviet Union. Though this saw an increase in the amount of exit visas granted by the Soviet Union, a proposal known as the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, which placed the condition of open emigration upon the agreement, caused the effort to backfire, and the amount of exit visas granted fluctuated greatly throughout the 1970s.

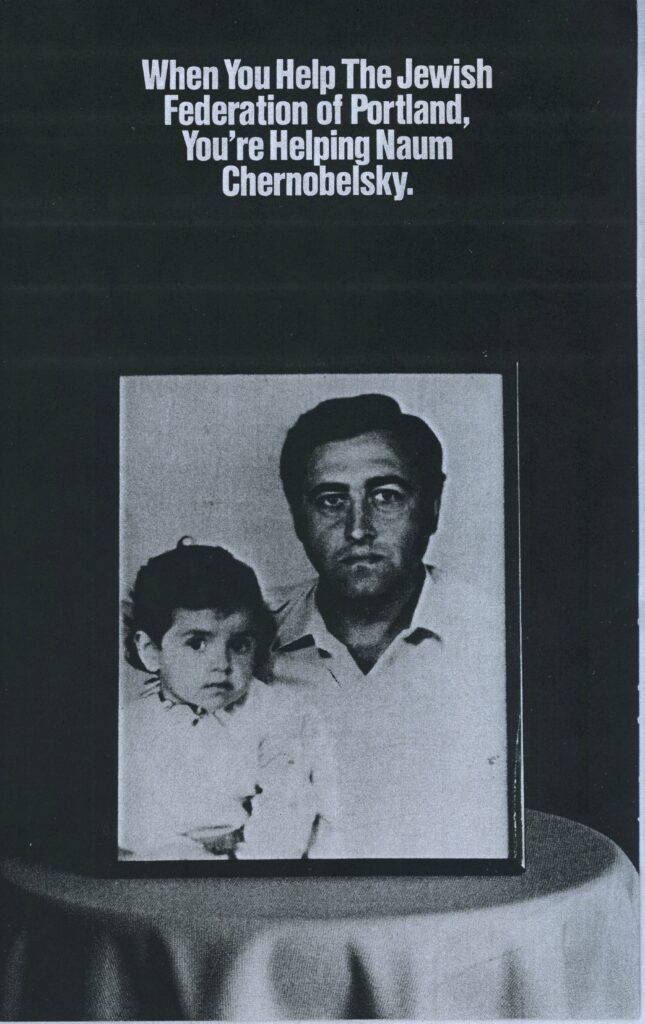

The first documented Jewish family from the Soviet Union arrived in Portland in 1973 (Schecter). The international group responsible for aiding in the resettlement of most Soviet Jews was the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), which helped Jews through transit camps in Italy and Austria and on to the United States (and Israel). Once immigrants reached the United States, the Jewish Federations throughout the country found places for resettlement.

Once these initial migrants had arrived with the help of the Jewish Federation of Portland, their presence provided the opportunity for more to come under the banner of family reunification. Many organizations were involved in the resettlement process at a local level; the Jewish Family and Child Service (JFCS), as the social organ, was the most prominent. During the 1970s, 60 families – 160 individuals – settled in Portland. Throughout the 1980s, relations between the US and the Soviet Union cooled again as the Salt II treaty failed to pass and President Carter boycotted the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games. However, Soviet Jews continued to arrive in Portland, and their number reached 1,000 by the end of the decade (Olsen 2010).

Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Portland spoke little English; according to Nora Lehnhoff, then director of JFCS, about half spoke a few phrases and only a handful had any kind of fluency. Unlike the immigrants from the Russian Empire, however, who spoke Yiddish and came from a poor agrarian background, the Jews from the Soviet Union spoke Russian or Ukrainian and were typically highly educated and from major cities. This distinguished Jewish migrants from many others. The Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization (IRCO), which typically helps newcomers with job placement, was presented with the challenge of finding high-level jobs for immigrants with advanced degrees in engineering, computer science, and medical science. The JFCS published a booklet, authored by Tanya Lifshitz, in both English and Russian which helped immigrants settle in and learn key phrases for job interviews. In addition to the JFCS and IRCO, many community members and organizations helped find job placements. Within a year most Soviet Jews were self-sufficient members of the community.

Religious organizations were crucial in awareness support of immigration and settlement. The Neveh Shalom Synagogue sponsored a Russian Cultural Club, and the Mittleman Jewish Community Center offered a year of free membership to Soviet families. However, after years of repression, many of the Soviet Jews were no longer religious and some were even unaware of many Jewish traditions. Though this created some tension with the religious institutions that had worked for their resettlement, Portland’s Jewish community remained active in the international campaign for Jewish emigration. Evidence of activism can be found at the Oregon Historical Society, including various mailings to members of the Jewish community detailing “Soviet Anti-Semitism” and a call for signatures on a “Letter of Conscience” to Soviet Authorities. A conference on anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union was also held at Reed College and various rallies in were staged in Portland throughout the 1980s.

The final wave of Soviet Jews occurred in the early 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Approximately 1,000 of these immigrants settled in Portland (Olsen 2010). Since then, Jewish migration from the FSU to the US has slowed considerably; in order to gain refugee status, migrants must prove “well-founded fear” of persecution, which has greatly diminished for Russophone Jews. Furthermore, the Jewish community in the former Soviet Union has become too small to be a major migrant source.

The FSU Jews of working age and their children typically learned English, though most first generation Americans of this community still learned Russian, as well, in order to communicate with grandparents and other older immigrants. Despite the common language, however, there has typically been minimal interaction between other segments of the Russophone community in Portland. Russian-speaking Jews tend to concentrate on the west side of the Willamette, where the traditional Jewish population base and institutions are situated. Most other Russophone groups tend to settle in outer southeast Portland and the surrounding suburbs.

Compared to other Russian immigrant groups to Oregon, Jews from the Soviet Union are relatively small in number. Their tendency to identify more with the Jewish community than other immigrant groups from Russia also contributed to the celerity with which they adapted to their American surroundings. While these immigrants are now largely integrated in the greater community of Portland, their history is well preserved by the Jewish institutions that aided in their resettlement.

Selected Bibliography:

Baron, Salo W. “Population.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. 2nd ed. Vol. 16. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2007. 381-400. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 9 July 2013.

Eisenberg, Ellen. “Transplanted to the Rose City: the Creation of East European Jewish Community in Portland, Oregon”, Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 19, No. 3, Spring 2000, Pp. 82-97.” Sage Race Relations Abstracts. 26.4 (2001). Print.

Hardwick, Susan Wiley. Russian Refuge: Religion, Migration, and Settlement on the North American Pacific Rim. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (1993).

Levin, Nora. The Jews in the Soviet Union since 1917: Paradox of Survival. Two volumes. New York: New York University Press (1988).

Lenhoff, Nora. Personal Interview. August 2013.

Lifshitz, Tanya. In the Beginning: An English-Russian Guidebook for New Immigrants. Portland, OR: Jewish Family & Child Services (1981).

Lowenstein, Steven. The Jews of Oregon (1850-1950). Portland, OR: Jewish Historical Society of Oregon (1987).

Miller, Alan. “Estimated Jewish Population in the Former Soviet Union (FSU).” Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union. July 2013. Web.

Nathans, Benjamin. Beyond the Pale: the Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press (2002).

Olsen, Polina. Stories from Jewish Portland. Charleston, SC: The History Press (2011).

Olsen, Polina. “Immigrants found new life in Portland.” The Jewish Review (July 2010). Schecter, Sylvia. “The Russian Coordinator and her job at the JF&CS.” Portland Jewish Review (May 1979): 8.

“Settling In.” Oregon Jewish Museum. Shoshanna Lansburg, Curators of Exhibits. Summer 2013.

Sorensen, D.J. “Strong Soviet-American Trade Links Urged.” The Oregonian (4 October 1972).

Staff. “Relieving Congestion in Russian Jewish Quarter.” The New York Times. 20 January 1907. Web.

Woloshin, Mara. “Getting Settled: Jewish Family and Child Service Helps to Build New Lives for Immigrants.” The Jewish Review (September 1989).

Woloshin, Mara. “Understanding the Difference: Soviet Immigrant? Soviet Refugee?” The Jewish Review (September 1989).